I have to admit that I am baffled by today’s parable from Jesus. I’m not alone. Like any good parable, there are as many possible angles in this one as there are people who attempt to interpret it. What are we to do with a rich man, a dishonest manager and a bunch of debtors in the hands of Jesus? If most of us were telling the tale, it would end with the manager facing charges, the debtors paying off all they owed and the rich man sitting pretty with plenty of cash and a new employee.

Instead the manager gets commended, commended!!! for being shrewd and we’re not even sure whether or not he gets fired in the end. The debtors get away with much of their obligation forgiven and the rich man… Well, what’s in it for him?

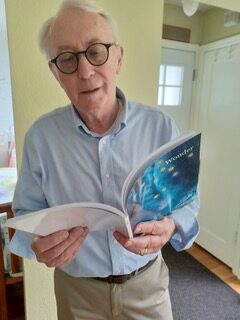

In Palmer Parker’s most recent book, which he’s writing in his 80’s, he reflects that it is bafflement that has led to his past 15 books. A holy bafflement has been at the root of his growth and some of his most powerful insights that he has shared through his writing and retreat leading.

This week’s bafflement, conversations and research into the parable of the dishonest manager have given me plenty to think about. It goes against everything I think is fair and right to hear about a dishonest man who has squandered money that doesn’t belong to him and, when he is about to get caught, doubles down by releasing some of the debt owed to his master. He should be punished, not commended. People should be made to pay what they owe. The rich man should use his power to bring the guy to justice.

But that’s not the way Jesus ends the parable. And there are clues throughout it that something more is going on. The first clue is in that word, squander. Jesus has just used it in another famous parable right before this one. That one is about a young man who asks for his share of his father’s wealth, his entire inheritance before his father has died. He leaves home, goes to a foreign country and squanders it all on wine, women and song. When he returns home, broke and begging, instead of turning him away or making him work it all off, the father gives him a royal robe and ring, puts shoes on his feet and hosts a celebratory meal. It’s baffling. He doesn’t even let that ne’er do well prodigal son apologize.

Then there’s the strange payroll practices in Jesus’s parable of the workers in the vineyard where everyone who works even one hour as a day laborer is paid the same full day’s wages as everyone else at the end of the workday. The folks who began at first light are outraged over a boss who doesn’t follow the rules of fairness even though they are given exactly what was promised. In so many of these parables, Jesus is messing with our sense of what’s right.

My morality tends to be pretty conventional. I follow the rules mostly unless I think I can get away with bending or breaking them and not getting noticed (like speeding and California stops.) I think things should be fair and that you should be rewarded for your hard work and decency (until I learn about how the college admission process is influenced by money and power). I believe in equality under the law although it’s become crystal clear to me that if your racial identification is anything other than “white” you will experience racial profiling and discrimination in our legal system.

Wait a minute. I’m already getting confused.

There must be something more going on here. Something that has to do with the forgiveness of debts; something to do with making friends and eternal homes; something about serving God and using money.

In this parable the manager ends up making friends and being commended by the rich man. The debtors end up having debt forgiven and being free from obligation. And the rich man is more than satisfied. He has not lost anything, even as others have gained favor, forgiveness and freedom.

The rich man, the prodigal father, the vineyard owner all are more concerned with relationship than they are with riches. In fact, they seem to have endless resources that they can choose to deploy for the benefit of others freely and without obligation. They bless and reward both the worthy and unworthy. They are more concerned with the restoration of relationship than they are with accurate accounting. These parables end with homecoming and celebration. They are parables of the Kingdom of a God who doesn’t act like any king, ruler, rich man or father most of us will ever meet. These are parables of Jesus’s God, parables of grace.

This is the grace of God in Jesus who hangs out with those who are dismissed as unworthy sinners. This is grace that shocks the religious and righteous with the willingness to approach the disgraced and the outcast, to forgive the offender, to share with those deemed unworthy. This is the grace that ultimately leads to the cross. It is the foolishness of Jesus who offers up all that he is and all that he has in radical trust that God will multiply that offering beyond all he can ask or imagine.

With his dying breath, Jesus will ask for the forgiveness of all our debts and make for himself and all of us an eternal home that can never be taken away.

These parables call into question so much of what we value and how we think the world should be. They baffle us. They make us uncomfortable. And they raise issues that we might prefer to avoid. I remember early on as a Christian I read some books by Tom Sine where he discussed the concept of profaning money. Most of the advice I get is about protecting money, making sure I have something in savings, making good investments and not wasting my money. That includes charitable giving. We’re encouraged to make sure the organizations we support use the funds reliably and well. There’s nothing wrong with that, but Tom’s idea is that there are times when we need to take away the power that money has over us, the getting of it, the worry over it, the control of it. There are times when you simply need to let it go, not knowing if the decision to give is wise or worthy. In other words, “Never resist a generous impulse.”

I think of that when I remember my first year here at St. Luke’s when our finances were absolutely desperate. We received an amazingly generous gift out of the blue, a gift that would enable us to move forward and ensure that our obligations would be met. The small Bishop’s Committee at the time was composed mostly of the folks who had gone through the really difficult times here and knew that the church was close to being closed. Before they spent the money, they decided they wanted to give 10% of it away in gratitude. I can think of many who would have counselled them differently in those circumstances but that generosity has continued to characterize this congregation’s approach and God has continued to provide beyond what we can ask or imagine.

Many years ago I squandered an advantage I had. I was a good student in High School, on the honor roll, a Merit scholar and voted “most intelligent” in my senior class. In my family it wasn’t wealth that was most highly valued but rather education and intelligence. I had both and they had become both my idol and my identity. But I was poor in relationships, poor in compassion, poor in spirit. When I became a Christian in January of my senior year, much began to shift. My priorities changed. And so, instead of attending an elite private school, I went to a public University where there was a greater diversity in the student body. Instead of pre-law I shocked my parents and counselors by majoring in Recreation and Park Management. I squandered my education, privilege and natural gifts.

At the time no one could figure out what I was doing and I’m pretty sure I didn’t even know myself. But in Christ I had discovered an abundant life that was about so much more than winning the prize, being the smartest and earning success. My choices led me into relationships with people who were different from me. I learned to care for folks on the margins, including the poor and disabled. I had time to make friendships, to learn to live in community. It turns out to be a very rich life.

How can we all engage in holy squandering? What can we let go of in order to make friends and build relationships? Where are we called to forgive debts even when the recipient is unworthy or unrepentant or doesn’t even realize how they have hurt us? When are we invited to the great celebrations of God’s grace and mercy? Will we accept the invitation or remain outside the door because we feel like it isn’t fair or right?